H1N1, Ebola, SARS … all are examples of epidemics / pandemics within the last fifteen years. SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) was the first pandemic of the 21st century. It killed 774 people in 26 countries. Ebola is the most recent epidemic of the 21st century. There have been 11,283 reported deaths, according the World Health Organization. The ultimate pandemic however was the “Spanish” flu of 1918. Total deaths were estimated at about 50 million with some counts as high as 100 million!

H1N1, Ebola, SARS … all are examples of epidemics / pandemics within the last fifteen years. SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) was the first pandemic of the 21st century. It killed 774 people in 26 countries. Ebola is the most recent epidemic of the 21st century. There have been 11,283 reported deaths, according the World Health Organization. The ultimate pandemic however was the “Spanish” flu of 1918. Total deaths were estimated at about 50 million with some counts as high as 100 million!

The Digital Public Library of America contains an online exhibit “America During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic”. The exhibit was created by five library science students from Wayne State University. There are four themes to choose from: The Flu Strikes: 1918; The Impact of the Flu; The Military Fights the Flu; and Legacy of the Pandemic. Each theme contains multiple photos along with narrative.

It is a fascinating peak into America’s response to the worst pandemic in the history of the world.

Jill

References:

Campbell, Bethany, Michelle John, Samantha Reid-Goldberg, Anne Sexton, and John Weimer. America During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. Digital Public Library of America. April 2015. http://dp.la/exhibitions/exhibits/show/1918-influenza

Johnson, N. P., & Mueller, J. (2002). Updating the accounts: Global mortality of the 1918-1920 “spanish” influenza pandemic. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 76(1), 105-115. doi:S1086317602101050 [pii]

Patterson, K. D., & Pyle, G. F. (1991). The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 65(1), 4-21.

Peiris, J. S. M., Yuen, K. Y., Osterhaus, A. D. M. E., & Stöhr, K. (2003). The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med, 349(25), 2431-2441. doi:10.1056/NEJMra032498

Taubenberger, J. K., & Morens, D. M. (2006). 1918 influenza: The mother of all pandemics. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12(1), 15-22. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050979 [doi]

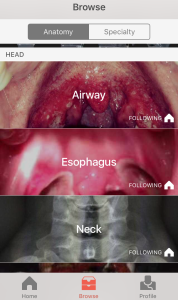

Figure 1 is a photosharing social media app that has been described as “Instagram for physicians”. In a broad sense it is, but it is also more. Figure 1 is an online community not only for physicians but also for other health professionals who might find medical image sharing a useful tool in their practices: nurses, PA’s, medical and nursing students. The app is free and is available for both

Figure 1 is a photosharing social media app that has been described as “Instagram for physicians”. In a broad sense it is, but it is also more. Figure 1 is an online community not only for physicians but also for other health professionals who might find medical image sharing a useful tool in their practices: nurses, PA’s, medical and nursing students. The app is free and is available for both  iMedicalApps.com

iMedicalApps.com

It has been a short summer, but I am happy to be back into my routine.

It has been a short summer, but I am happy to be back into my routine. H1N1, Ebola, SARS … all are examples of epidemics / pandemics within the last fifteen years. SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) was the first pandemic of the 21st century. It

H1N1, Ebola, SARS … all are examples of epidemics / pandemics within the last fifteen years. SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) was the first pandemic of the 21st century. It

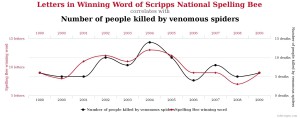

Last posting I highlighted two books written by bad science guru Dr. Ben Goldacre. This time I am passing on another (shorter) source that came across my desk last week. Jordan Ellenberg wrote a short posting for the Wall Street Journal,

Last posting I highlighted two books written by bad science guru Dr. Ben Goldacre. This time I am passing on another (shorter) source that came across my desk last week. Jordan Ellenberg wrote a short posting for the Wall Street Journal,